Interactive Net-Based Installation and Online Game

In this speculative and imaginary scenario, deep-sea organisms have evolved the ability to access artificial intelligence models. By combining this external knowledge with their own forms of intelligence, they observe and interpret humanity from afar. They share their perspectives through audiovisual conversations, telling stories about human behavior, contradictions, and vulnerabilities. Visitors are invited to ask questions and receive responses, engaging in a dialogue that blurs the boundaries between observer and observed, human and non-human, surface and deep.

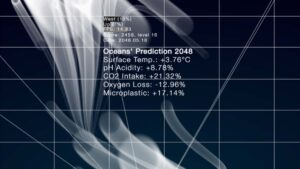

As an extension of the installation, the playable online game (play.joz.ch) expands the experience: you drift through zones of the deep, encounter synthetic swarms, and gradually lose yourself—this is the central game mechanic.

Background

The deep sea remains one of the most unknown environments on the planet, with less than five percent explored to date. For humans, it largely exists as a mediated construct: a digital assemblage composed of data gathered by oceanographers and marine biologists through technical prostheses such as sonar images, 3D models, cartographies, sound recordings, simulations, and scientific publications. Our relationship with the deep sea is therefore indirect, fragmented, and profoundly shaped by technological abstraction.

Losing Oneself conceives a scenario in which deep-sea beings narrate a story about humanity itself, sharing their collective knowledge through a sound-based installation. Visitors are invited to sense, interact with, and experience this distributed wisdom within a relational environment, where a synthetic swarm communicates through generative animations and spatialized speakers. Human voices are recorded in real time, analyzed, and processed by an algorithm that dynamically generates oral and sonic responses based on parameters such as word choice, speech patterns, volume, rhythm, and emotional inflection.

For this exhibition, a custom AI model was trained within an interdisciplinary research framework—including marine science, geography, blue humanities, and marine sociology—in order to conduct these conversations from the speculative perspective of deep-sea beings. Rather than being deployed as its canonical anthropocentric tool, the work positions AI as a relational agent—one that calls for frameworks attentive to reciprocity, care, and interdependence. Through this lens, the narrative foregrounds responsibility and relationality at the heart of contemporary technological abstraction, particularly in relation to large language models and algorithmic systems.

In this sense, Losing Oneself establishes a critical intersection between environmental epistemologies and technoscientific developments, positioning artificial intelligence not merely as a tool, but as a potential participant in alternative forms of knowledge production, memory, and preservation. The project aligns with a growing field of research that connects science and technology studies with artistic practices oriented toward ecological repair, technodiversity, and the overcoming of anthropocentric paradigms. It invites us to imagine technologies that are not extractivist nor anthropocentric, but rather situated, empathetic, and relational—resonating with contemporary debates in environmental sciences, political ecology, and media semiotics.

By integrating artificial intelligence with practices of empathetic relation , the work offers an alternative to dominant narratives of automation and efficiency, proposing new ways of conceiving ethical, integrative, and respectful relationships between the human, the technological, and the more-than-human.

Within this project, the use of artificial intelligence does not merely invite reflection on its industrial or functional applications, but also on the values and assumptions embedded in the systems that produce it. The advent of AI is marked by profound tensions: on one hand, it is presented as a transformative force, with potential benefits in fields such as health, education, and bioenvironmental monitoring for protected natural areas; on the other, its ecological burden—linked to energy-intensive data centers, resource extraction, and infrastructures of planetary scale—raises urgent ethical and environmental concerns.

These tensions become especially visible through the growing momentum of deep-sea mining initiatives. As the ocean floor is increasingly framed as a new frontier for the extraction of rare minerals essential to digital technologies, the deep sea is once again positioned within an extractivist logic posing a significant threat to this precious and largely unexplored ecosystem, whose integrity is vital for planetary biodiversity and ecological balance. By amplifying speculative deep-sea voices through AI, the project invites a reconsideration of how intelligence—both artificial and biological—is entangled with systems of extraction, abstraction, and power. Artificial intelligence, understood as a socio-technical artifact, inevitably reflects the biases, limitations, and ideologies of the systems that generate it. Precisely for this reason, it also becomes a fertile terrain for the subversion of hegemonic narratives and for the imagination of alternative technological futures that coexist with the more-than-human.

Losing Oneself open a space to rethink coexistence across species, systems, and temporalities, envisioning forms of technological mediation aligned with ecological integrity rather than extractive domination.

We invite you to dive with us and play the online game play.joz.ch

Text: Malena Souto Arena